OUR SECURITY ANALYSES

View security analysis

Port Sudan at the Crossroads of the Drone War

Long spared by the fighting, Port Sudan has now become a mirror of a conflict gradually engulfing...

Wagner and Africa Corps in West Africa: Security Implications of Russia’s Presence

Africa’s Evolving Security Landscape West Africa and the Sahel are undergoing a profound reconfig...

Terrorism in Nigeria: Evolving Strategies and Reintegration Policies

In response to the persistent attacks by terrorist groups across Nigeria, the government is incre...

Terrorism in the Sahel: How Do Jihadist Groups Acquire Their Weapons?

During the March 28 attack in Diapaga, Burkina Faso, jihadists seized a large quantity of weapons...

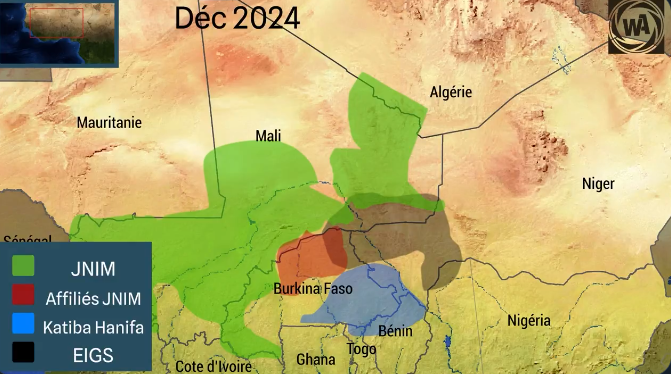

JNIM in the Sahel: Recent Developments and Area of Influence

JNIM is one of the most influential Islamist terrorist organizations in the world. As of 2025, th...

Military FPV drone: a growing threat in West African conflicts

FPV drones have made their appearance in conflicts in West Africa and the Sahel. Terrorist groups...

Terrorism in Burkina Faso: The Army Struggles to Contain the Jihadist Threat in the North

Since January 30, 2025, Burkina Faso’s northern Soum province has suffered seven terrorist attack...

Terrorism in the Sahel: The Limits of State Cooperation

"Africa remains the epicenter of global terrorism," lamented Amina J. Mohammed, Deputy Secretary-...

Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs): carnage in Mali and Burkina Faso

In Mali and Burkina Faso, improvised explosive devices have become the weapon of choice for terro...